BRIAN’S ILLUSTRATED LIFE STORY

chapter 2

EARLY LONDON YEARS:

THE SLADE SCHOOL OF ART AND

FIRST COMMISSIONED ILLUSTRATIONS

1950 - 1961

- AT THE END OF EACH PAGE IS A LINK TO THE NEXT -

THE SLADE SCHOOL OF ART - A NEW LIFE FOR ME

“I felt very uneasy during my first year of living in London. I missed the sense of solidarity I had grown up with in a close Yorkshire mining community. In those days only 3% of working-class boys and girls went to university. The gap between my environment and theirs was clearly apparent and I was oversensitive towards the class-ridden society I was now confronted with. I had nothing in common with my peers and I would become unnecessarily awkward when in conversation, because of my accent that people couldn’t understand. Even the digs I found in my first year proved unmistakably unsuitable. As a student, studying art and wanting to paint, I had a landlady obsessed with maintaining her house in a “perfectly spotless condition.” I could not even sharpen a pencil for fear of upsetting her with what she saw as, “the disruption of the order and cleanliness of her property.” I moved out the following year to Cato Street in Clapham to share a room with Hugh Jones and Rex Pickering, who remained my very good friends for years after University. In retrospect they were glorious and happy times.

Brian, who could easily have been described as a round peg in a square hole at the Slade School of Art in June 1950.

Reproduced with kind permission from the Slade School of Art, UCL.

“I had three years just painting, eating, drinking and studying art, reading nothing but books about art and looking at nothing but art. During my lunch hours, I would go to the National Gallery. Astonishingly, at that time, one could ask to see drawings and etchings by Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo and they would be brought out and laid before one to be studied, admired, even touched! It seems almost unbelievable today. On Saturdays I would play cricket for University College London’s first XI and on Sundays visit Aurélie, who had come back to London’s Maida Vale with her parents, her ageing father now suffering the consequences of a shrapnel leg wound from WWI. I remember us hand in hand walking the streets of London, going to the cinema once a fortnight, thinking of our future marriage.

“Like many students I was always short of money and art materials were very costly, so during the summer holidays I worked at Lyon’s ice cream factory in Hammersmith (London) and cut wheat with a scythe back home on a farm near Hoyland Common. Over the Christmas period I joined the post office team, which allowed me to buy a few presents for my family, as well as the compulsory bottle of sherry!

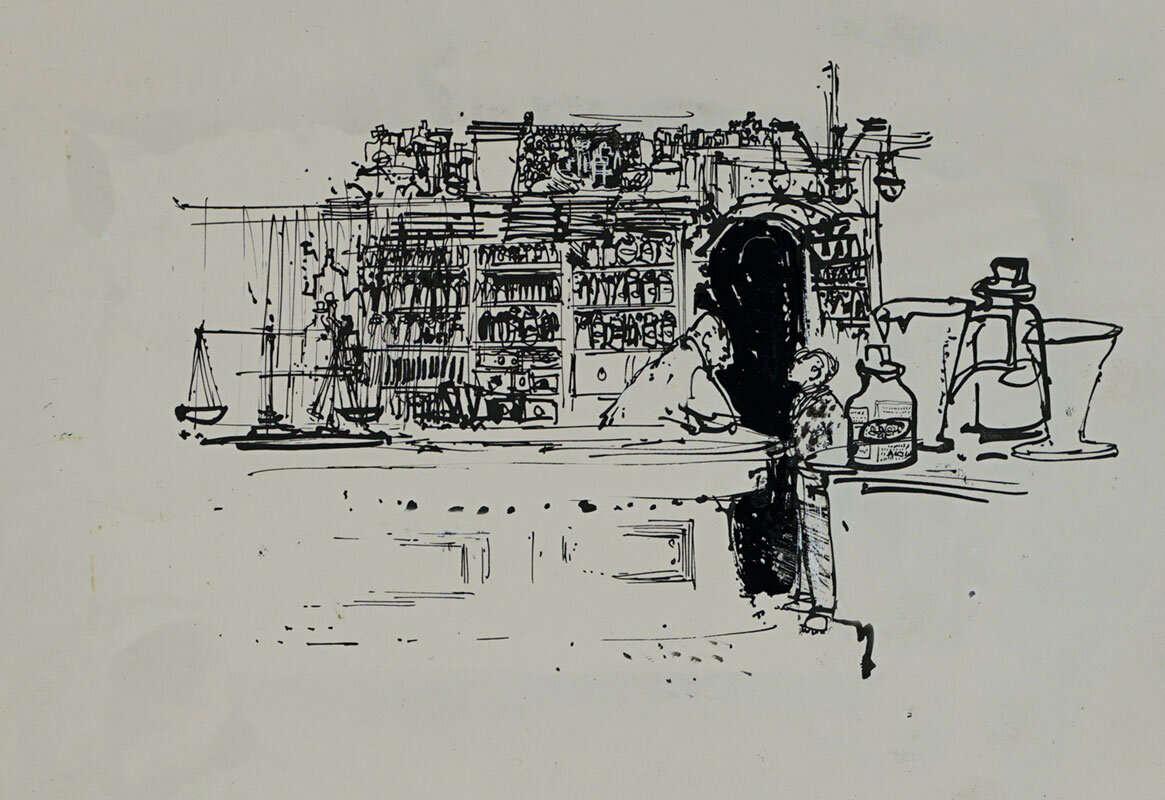

A selection of drawings and one etching from Brian’s time at the Slade School of Art: 1949 - 1952.

“The course I followed at the Slade gave me a sound foundation within the artistic world, but in retrospect and had circumstances allowed, I would have benefited far more had I applied five to eight years later. I was only nineteen at the time. I drew quite well there, but my painting showed definite signs of confusion, perhaps in part due to the fact that I found myself living in a totally alien environment. I had lost any artistic bearings I may have previously acquired and the contrary teaching methods employed by the college disoriented me. On the one hand students were very much left alone to discover their personal direction within the field of painting, an attitude I now find essential for the development of a mature student’s creative senses. However, on the various occasions I required guidance, I was met with unsatisfactory and insensitive tuition. Lucien Freud, William Coldstream and Claude Rogers, my tutors, were established artists and yet an artist however great, does not necessarily make a great art teacher. People like Picasso and Matisse, that I greatly admired, were poisonous names in establishment circles in the UK at this time. I remember the President of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Mannings, saying if Picasso showed his face in this place he would personally kick his arse out of it. How times have changed!

“I left the Slade three years later, in 1952, with a Diploma in Fine Arts, today called a BFA. Despite any earlier judgments, today I can honestly affirm the Slade was probably the finest establishment for fine art in the world.

TEACHING MATHS AT MUSIC SCHOOL AND MARRIAGE

“It wasn’t long before I received my military service call-up papers, which instructed me to report to the Royal Artillery Corps. There was no way I would become cannon-fodder so I rang the War Office on the spot, to adamantly voice my objection. “My dear lad, do you realise you are speaking to the Army!” was the authoritarian response I got. However with a little more persuasion from my side, I was invited to appear at headquarters where my request for a transfer to the Educational Corps was met, thank goodness, by a sympathetic ear. Funnily, this is how I became an education sergeant at The Royal Military School of Music, not to teach music, though, but mathematics! I was posted there for two years and all my students failed!”

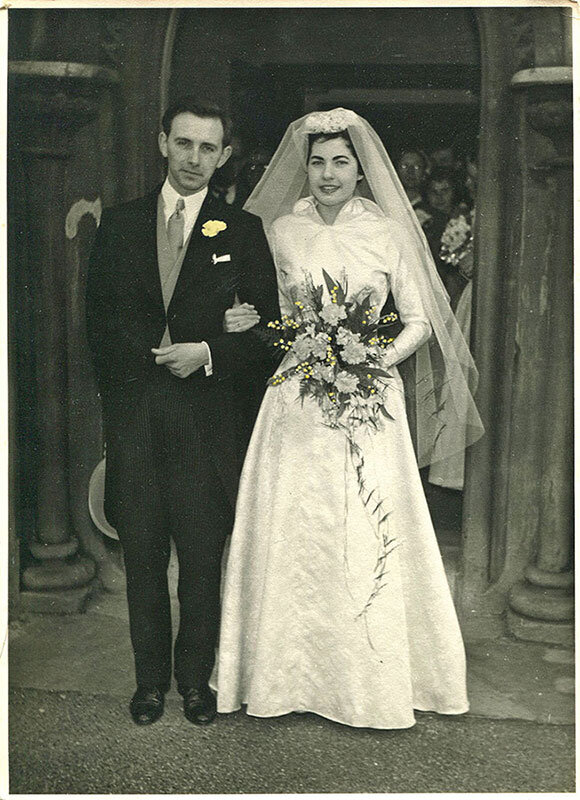

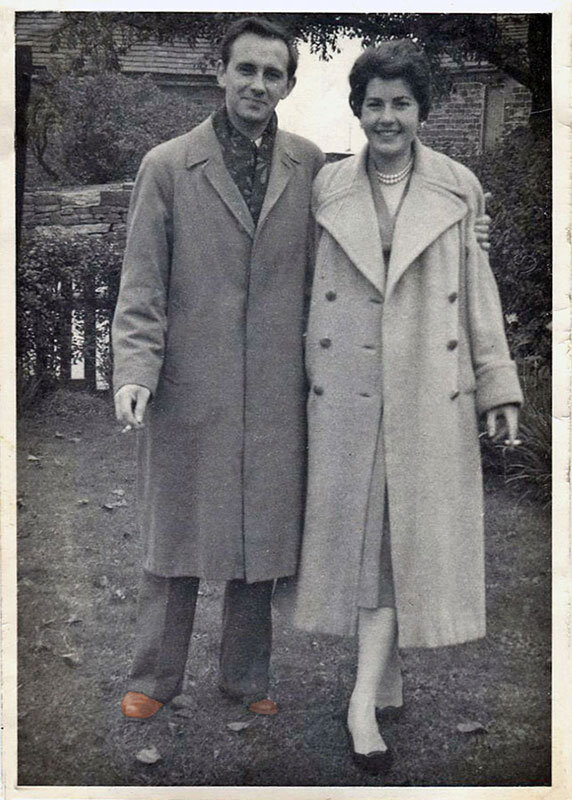

After Brian’s military service, he and Aurélie decided to get married, setting the date for 2nd April 1955. Thereafter, every year, on or around the 1st of April, Brian would receive a written reminder for the following day’s anniversary from a mysterious and anonymous friend living in England, to not forget this special date, as he could be very forgetful. Could Aurélie have been behind this?

Before they married, our mother was both a buyer and a model at Harrods department store. She catered for ladies of means with a craving for high fashion but lacking the buying power for Haute Couture. In the very private ‘Dress Room’, exclusively dedicated to this select clientèle, Aurélie would parade down the catwalk, with all the attributes of a professional model, wearing the impeccably tailored garments she had selected for her clientèle. She was stunningly beautiful.

2 of 150 fabric designs Brian created after leaving the Slade.

In the series of Brian’s curious postings, the next one was as an art teacher at Selhurst Grammar School in Croydon from 1955 to 1957. Curious because his candidature had doubtless been approved more for his ability to play the piano and cricket than for his artistic skills. What the school really needed was someone to play the organ at morning assembly. That, and improve the level of the school’s cricket team!

29 000 BOOK TITLES

Although they were both working, money was still short. “I had read somewhere,” said Brian, “that 29,000 book titles were published on average each year in the UK. Many of these would need illustrating. I began to wonder how I might start making pictures for books. Well, it seemed that the thing to do was to design book wrappers. I taught myself lettering and calligraphy and created my own designs based on books I had read. In those days, there was no full-colour book cover production. It was all two, three, or four-colour printing. You had to draw or paint every colour separately and on a different piece of paper and then they all had to be combined to produce a polychrome image. But it was a marvellous introduction into the techniques required for producing works for books.

THE DAFFODIL SKY, MY FIRST BOOK WRAPPER COMMISSION

Brian’s very first book wrapper commission was provided by Victor Morrison at Michael Joseph Ltd in 1955

A perfect example of three way colour separation.

“Every day, I would line up my pupils at five minutes to four and as soon as the bell rang, I would be the first out of school, portfolio in hand, ready to jump on my Lambretta scooter and career frantically through the streets of London in order to arrive at various publishers’ doors before five o’clock, closing time. Victor Morrison, the Art Director at Michael Joseph Ltd, gave me my first book wrapper commission. It was for The Daffodil Sky, a collection of short stories by H. E. Bates.” Brian had found the luck that sometimes comes to the innocent, the talented and the persistent in an almost burlesque scenario. “As I entered the Art Director’s office,” commented Brian, “I found a man, his feet up on his desk, wearing neither tie, nor jacket nor shoes. He was dictating something to another man wearing a bowler hat, a rolled umbrella by his side.

“Do you mind if I shave?” he inquired looking at my work, his face covered in soap. “You’re not bad! We want a three-colour separated book jacket. Can you do that?"

“0h... yes," I responded.”

"And bleeds too?” he added in return.

“Bleeds I thought? I'd never heard of bleeds, but I answered favourably and got the job.”

The book was published in 1955 and that was the beginning of Brian Wildsmith as a ‘Freelance Artist.’ For years he and Aurélie lived on book jackets at £20 a throw in pre-decimal pounds sterling, approximately £450 in today’s money. We believe there are at least 84 book titles for which Brian either created the book wrapper, or illustrated the stories and or the chapter headings. Indian ink was always his primary medium for these, even though he did use colour of course, whenever required for the covers. Printing costs were much higher in those days and only larger format, and more expensive ‘coffee table’ books contained colour reproductions throughout.

27 book covers from the 84 that Brian illustrated in the 1950s and 60s.

Click on images to see enlarged

The only known review we have found that covers this period of Brian’s work, is a torn, unsigned article of unknown provenance found in Brian’s archives. The critic had written: “Indian Delight by R. J. McGregor, published in 1958, anticipates his painterly exuberance as a colourist by a number of years, while The Story of Jesus by Eleanor Graham and published the following year, shows his mastery of line in what was to develop into a recurrent and lifetime engagement with biblical themes.

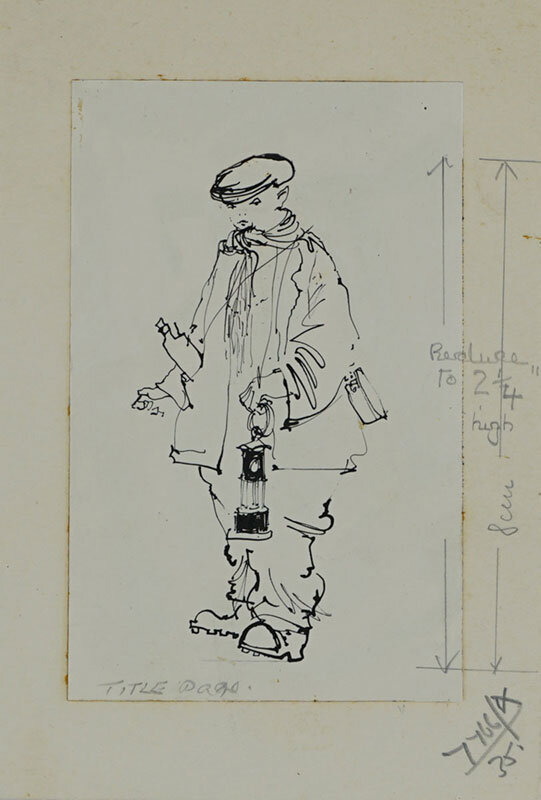

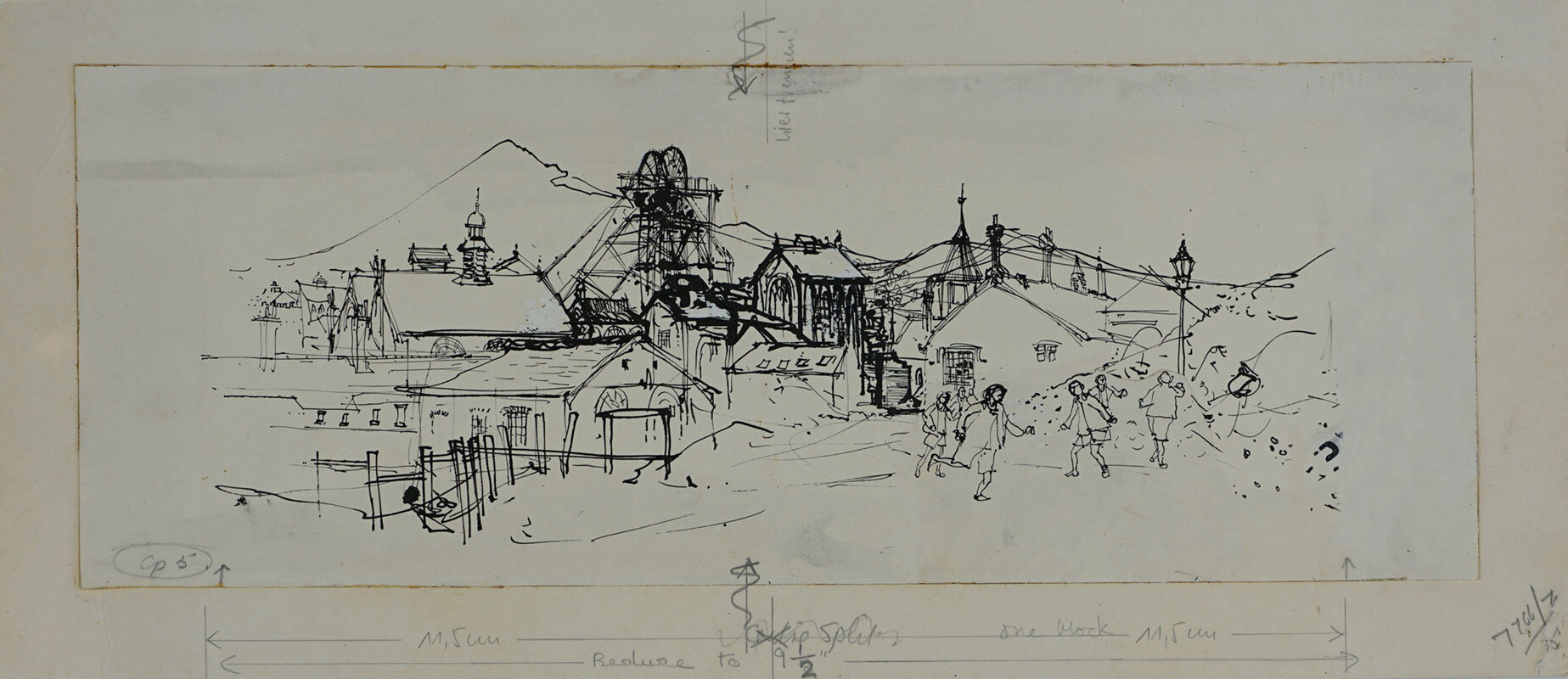

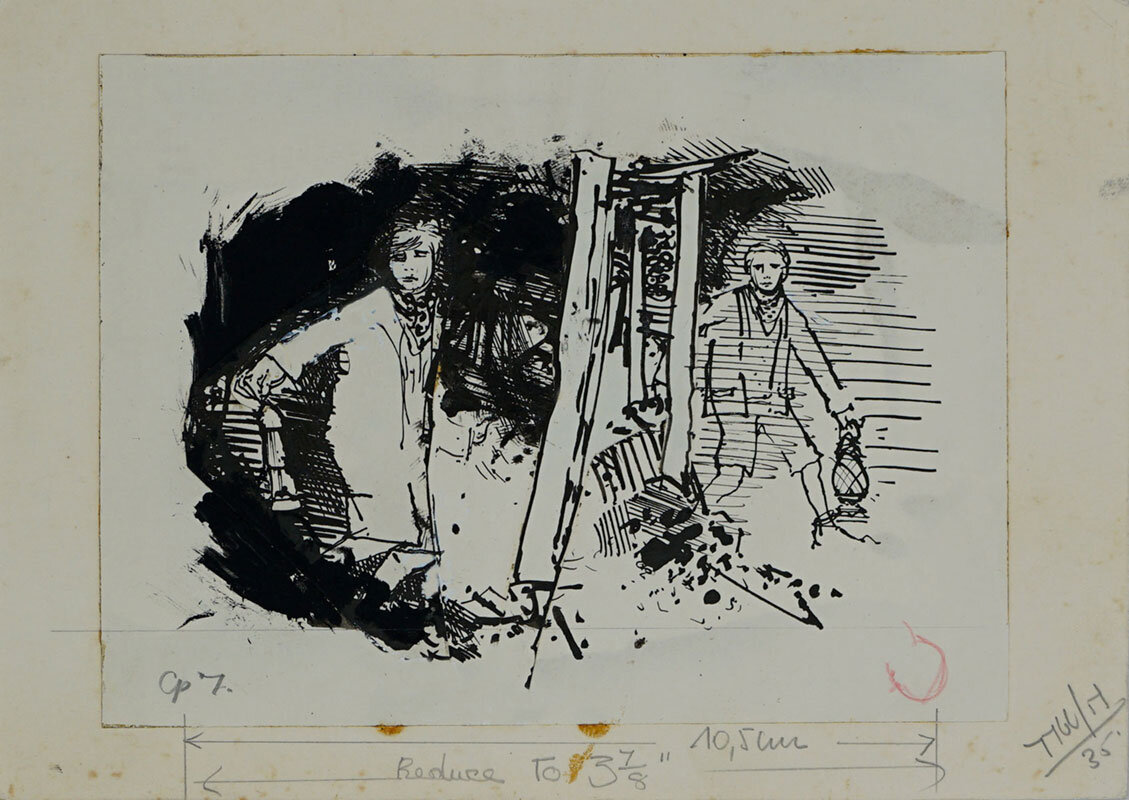

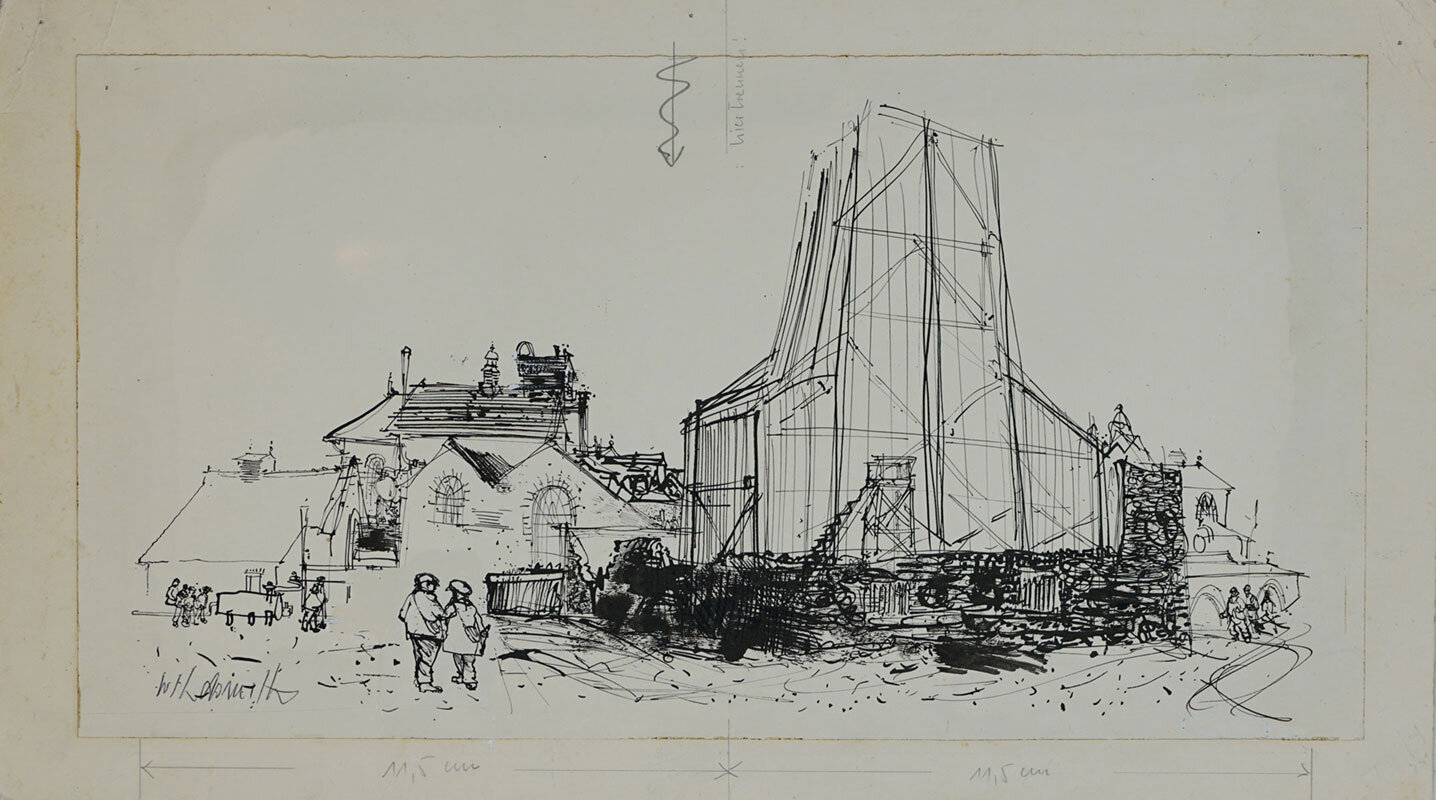

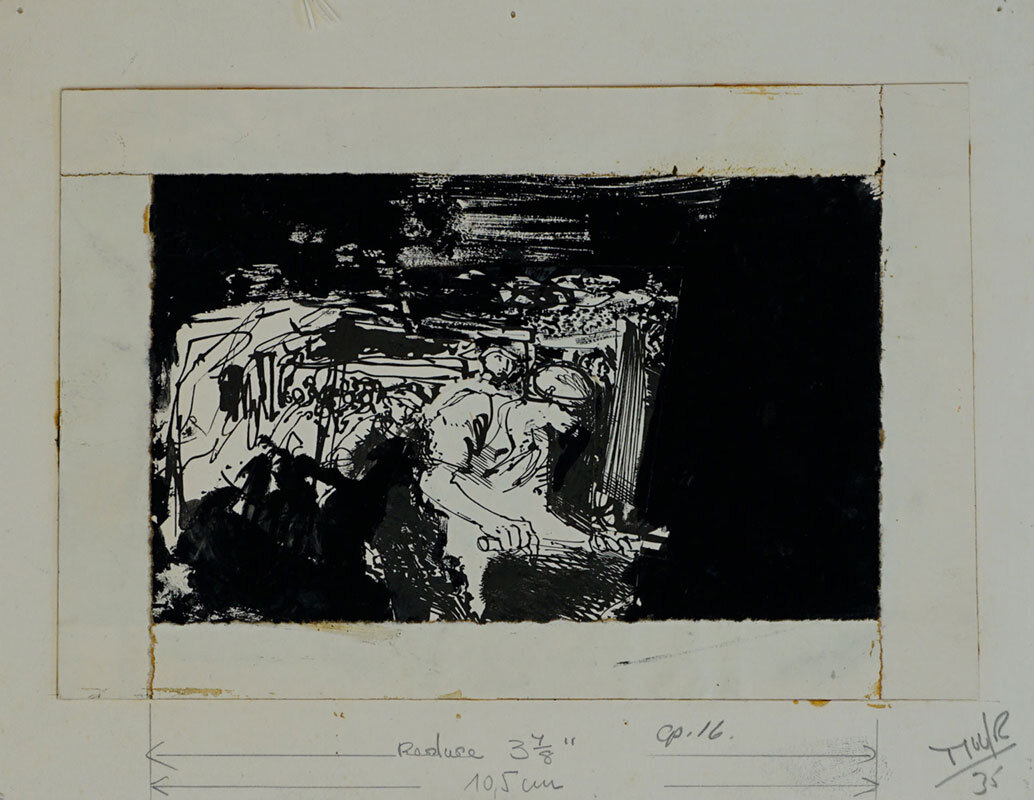

In Frederic Grice’s The Bonny Pit Laddie, 1960, (further below) Wildsmith was confronted with the settings and subject matter of his own childhood, (if you replace the central character Dick’s age of 12 years with 14, that of Brian’s father Paul, and they both had to go down the mine due to tragic circumstances, where their first task was to look after the pit ponies) inspiring one of his most committed ventures into narrative book illustration… In contrast, his powerful designs for The Oxford Illustrated Old Testament show by then he had moved towards a near symbolic language through which to communicate universally with younger children.”

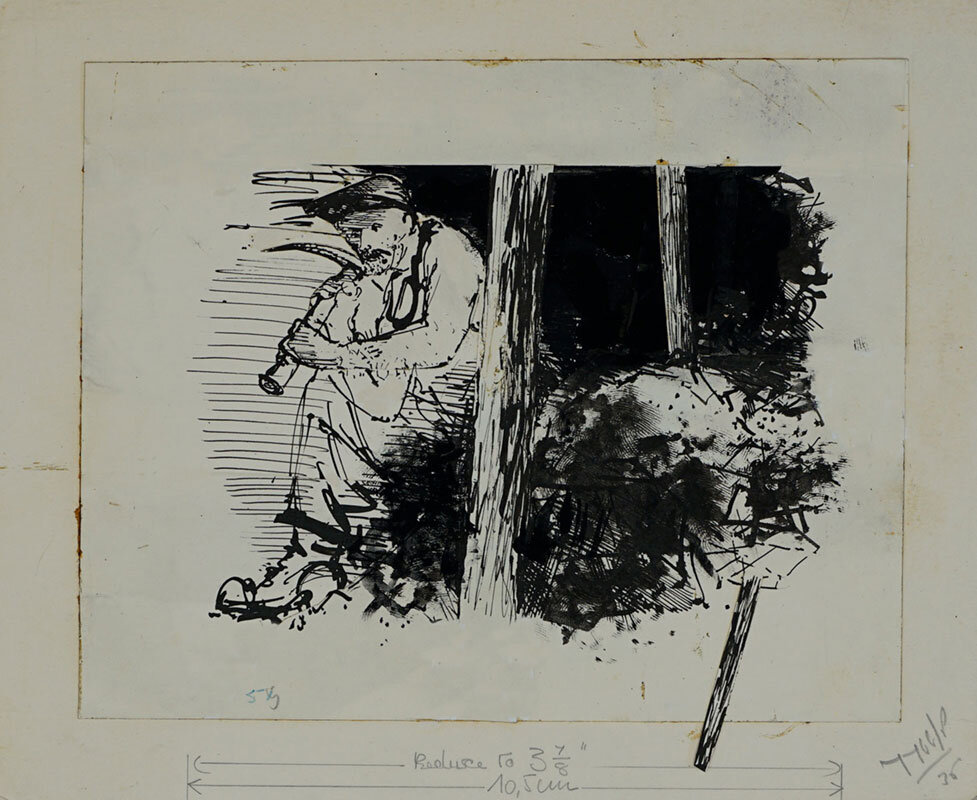

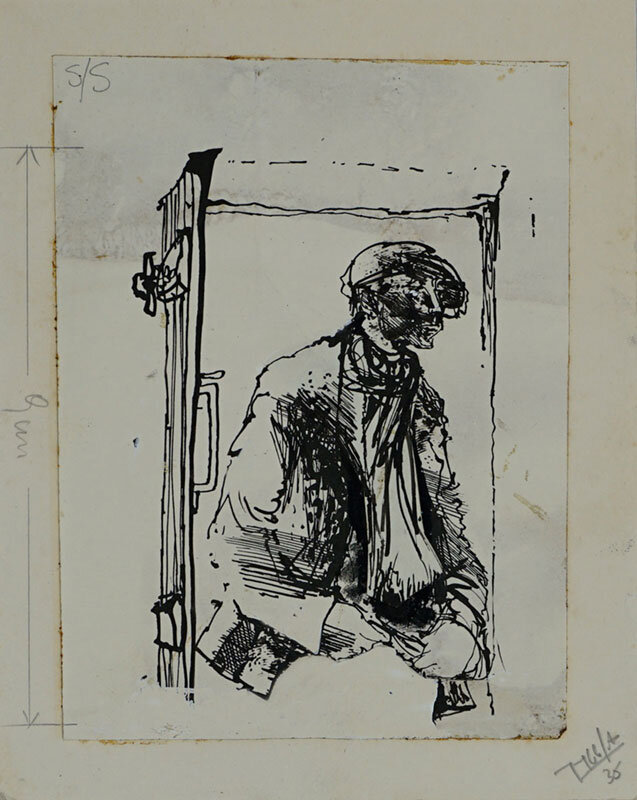

A selection of ink drawings from a variety of other authors’ books that Brian illustrated in the 1950s and early 60s in the years before creating his own titles.

Many more can be viewed in Early Work

Some of Brian's invoices for illustrations provided to a variety of publishers in the 1950s & 60s.

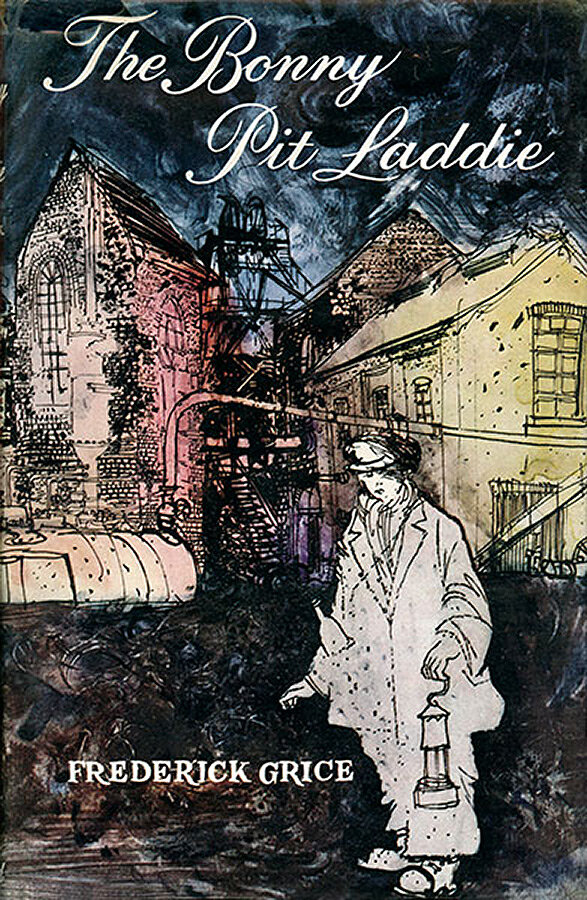

THE MINING WORLD

The mining world Brian had managed to physically escape dwelled on his mind throughout his life. One could even say that he was traumatised by it in so far that he fully realised that for one or two missed occasions or opportunities, he too might have been swallowed up and devoured in its hot, suffocatingly dark seams. He had so closely witnessed the devastating conditions in which his father had worked and the hardships he and his fellow colleagues had endured. We remember how viscerally affected he was throughout Margaret Thatcher’s long and brutal handling of the miners during the 1984 & 85 strike. He may have been following events on television and from afar, yet his empathy was born of a first hand knowledge, experience and understanding that none of us could possibly share. His father had a thunderous cough throughout his entire adult life and eventually passed away from pulmonary complications due to pneumoconiosis, or black lung as it was commonly called… killed by coal. In The Bonnie Pit Laddie, Brian was in a sure-footed place to portray these realities through his drawings.

The Bonnie Pit Laddie by Frederick Grice, illustrated by Brian Wildsmith. Oxford University Press, 1960, is a ‘brilliant evocation of Durham mining village a century ago.’

Also published as Out of the Mines: the Story of a Pit Boy. Franklin Watts, New York, 1960.

Rapidly, he was commissioned to produce book wrappers for a number of publishers which he would work on during the evenings, as he was still teaching at Selhurst grammar school. “These early drawings rank with the very best of contemporaneous work,” wrote Douglas Martin in The Telling Line, 1989, published by Julia MacRae Books, which contains essays on fifteen contemporary book illustrators. “After a year of working freelance,” said Brian, “I had earned twice what I earned in full-time employment but still felt both financial insecurity, as well as a general sense of frustration, always reaching out for more time.”

TEACHING ART IN FRUSTRATION

From 1960 to 1965 Brian became a member of William Stobbs’ team of teachers at Maidstone College of Art, (today known as Kent Institute of Art & Design) lecturing one day a week. Despina Meimaroglou, one of his students at the time, and today a multi-disciplinary and most interesting artist recalls: “From day one Brian Wildsmith was the teacher who stood by me, believed in my talent and gave me a lot of encouragement, and he continues to be a role model and mentor so many years on.” In his role of illustrator, Brian did not see himself continuing long in the situation where the author carries all the success of the book and the illustrator, as freelance accompanist, receives a flat rate fee. He was above all a painter with the drive to become recognised as a picture book artist and determined to make a living doing so.

Our mother with Clare, the eldest of her four children. Our mother did not reveal her first pregnancy to her husband until he had given up his day job in order to do what he loved: Paint and draw full time. To have done so earlier, she knew, would most probably have compromised his decision.

After three years enduring her husband’s frustrations, teaching by day and designing book jackets by night, Aurélie said to Brian, “Why don’t you just give up teaching and do what you really love - draw and paint full time.” Shortly after that conversation said Brian, “I came home from work one evening and told Aurélie, “I have resigned,” and she replied, “I’m pregnant!” What a beautiful, generous and fantastically supportive gesture that was! For she knew that if I had known earlier that she was going to have a baby, I would never have given up my day job for reasons of financial insecurity.”

MESSIANIC MABEL GEORGE

The way in which the premises of Brian’s art ambitions were to be realised, resulted from his approaching Oxford University Press and his first meeting in 1957, with their children's book editor, Mabel George. She was to play a major part in the development of Brian’s career as a creator of picture books. A printer’s daughter herself, Mabel had joined Oxford University Press in 1946 as a production assistant. She recalls in The Calendar, 1975, published by The Children’s Book Council, “My intention, ever since taking over the Oxford list for children in 1956, was to widen its range and to develop picture books at least equal in quality to the novels that we were producing.” Referring to the new electronic colour separating technology she wanted to use, she added, “I knew the quality of colour reproduction and printing in these picture books would also have to be improved. It was while searching for a printer who would co-operate with me in taking this branch of publishing seriously, that Brian Wildsmith was announced as ‘next’ in the long line of artists to stream through our office, hoping for books to illustrate. Here was a young married artist, a painter, teaching unruly boys and hating it, longing to paint and hoping, through book illustration, to earn the freedom to achieve his ambition. Looking at the abstract paintings of Sussex hop fields he propped against the wall, I saw how boldly yet delicately the colour was used, how poetically and simply the imagination behind the painting was expressed.”

Above: Three of the paintings we suspect Brian took along to his first meeting in 1957 with Mabel George at Oxford University Press, that lead to a more than 50 year collaboration with six different Children’s Book Editors.

TALES FROM THE ARABIAN NIGHTS

“Without divulging the hopes I had set upon him, I let him further learn the discipline of the book through more pen and ink illustrations and the occasional wrapper. When, at last, I established contact with an Austrian fine art printer who could print the kind of books I aspired to publish, and having recognised the glorious freedom and unconventionality in Brian’s use of colour, I commissioned him to produce fourteen colour plates for a new edition of the Tales From the Arabian Nights.

10 original illustrations from the Tales From the Arabian Nights, Oxford University Press 1961

“The printed result was highly satisfactory, pleasing the artist, most of the public and me. The fact that the work received criticism as well as praise was in itself encouraging. At last, the artwork in a children's book was being noticed and judged for its own sake. That decided it! I knew there and then that Brian was the one! With Oxford University Press’ backing, I invited him and his daring sense of colour to make his first picture book: an ABC to be printed by Brüder Rosenbaum in Vienna.”

Continued - CHAPTER 3 : 1962 - 1971 : HIS AWARD WINNING ABC TO THE MOVE TO FRANCE

Back to previous chapter - 1930 - 1949 : THE YORKSHIRE YEARS - FROM CHEMISTRY TO ART SCHOOL